William Wallace & Robert The Bruce: The Legends of Medieval Scotland

Together they embody the fierce, unyielding spirit of a nation fighting for its very existence against a powerful southern neighbour.

In the misty annals of Scottish history, few names burn as brightly as those of William Wallace and Robert the Bruce.

In the misty annals of Scottish history, few names burn as brightly as those of William Wallace and Robert the Bruce.

Together they embody the fierce, unyielding spirit of a nation fighting for its very existence against a powerful southern neighbour.

One was a lowland knight turned outlaw guerrilla; the other a nobleman who committed regicide and crowned himself king.

Both became immortal symbols of Scottish independence, yet their stories blending documented fact with layers of later legend, most famously through the 1995 film Braveheart (however much it took liberties with history).

The Wars of Scottish Independence: A Quick Context

When Alexander III of Scotland died in 1286 after falling from a cliff, he left no direct heir. The ensuing succession crisis triggered English intervention.

Edward I of England, known as “Longshanks” and the “Hammer of the Scots,” saw an opportunity to bring Scotland under English overlordship. By 1296 he had invaded, deposed King John Balliol, and placed Scotland under direct English rule. What followed was nearly thirty years of brutal warfare that forged the modern idea of Scottish nationhood.

Into this furnace stepped two very different men.

William Wallace: The People’s Champion

Born around 1270, probably at Elderslie in Renfrewshire, William Wallace came from minor gentry stock (his father was a crown tenant, not the peasant portrayed in popular myth). Almost nothing certain is known of his early life. The first reliable record of him appears in 1297, when he murdered William de Heselrig, the English sheriff of Lanark, supposedly in revenge for the killing of Wallace’s wife (or lover) Marion Braidfute. This story, however, appears only in the 15th-century poem by Blind Harry and is almost certainly romantic invention.

What is certain is that Wallace rapidly became the leader of a growing guerrilla insurgency. In September 1297 he achieved the impossible: at Stirling Bridge, with Andrew Moray as co-commanding, Wallace’s spearmen annihilated a larger English army under John de Warenne, Earl of Surrey. The victory sent shockwaves through Britain. For a few months Wallace was guardian of Scotland, knighted, and styled “Commander of the Army of the Kingdom of Scotland in the name of the famous King John” (Balliol).

English retribution was swift. Edward I returned from campaigning in France and crushed the Scottish army at Falkirk in July 1298, using Welsh longbowmen in devastating combination with heavy cavalry. Wallace escaped the field but resigned the guardianship. For the next seven years he waged hit-and-run war and conducted diplomacy in France, and remained the most wanted man in Britain.

He was finally betrayed in 1305 near Glasgow, taken to London, and subjected to a show trial for treason (ironically, since he had never sworn allegiance to Edward). On 23 August 1305 he was hanged, drawn, and quartered, and beheaded; his limbs were displayed in Newcastle, Berwick, Stirling, and Perth as a warning. The savagery of the execution only magnified his martyr status.

Robert the Bruce: From Compromiser to King

Robert Bruce (1274–1329), eighth lord of Annandale and later Earl of Carrick, belonged to one of the most powerful Anglo-Norman families in Scotland. His grandfather had been a claimant to the throne in 1291–92. Bruce initially supported Edward I, then switched to the Scottish side, then switched back again (pragmatism that earned him distrust from both north and south of the border).

Everything changed on 10 February 1306. In Greyfriars Church, Dumfries, Bruce met his main rival for the throne, John “the Red” Comyn (nephew of the deposed King John Balliol). The meeting ended in a quarrel; Bruce stabbed Comyn before the high altar. Excommunicated for sacrilege, Bruce had no choice but to go all-in. Six weeks later, on 25 March 1306, he was crowned Robert I at Scone in a hurried ceremony (the Stone of Destiny having been removed to Westminster by Edward I, they used a substitute).

The early years were disastrous. Defeated repeatedly, Bruce became a fugitive king, hiding in the Western Isles and (according to legend) drawing inspiration from a persistent spider while sheltering in a cave on Rathlin Island. By 1309 he had rebuilt his forces through guerrilla tactics learned, ironically, from Wallace’s example.

The turning point came on 23–24 June 1314 at Bannockburn, near Stirling. Bruce’s 6,000–7,000 men faced an English army perhaps twice as large under Edward II. Using clever terrain, schiltron spear formations, and a timely charge by camp followers mistaken for fresh reinforcements, the Scots won a crushing victory. Edward II fled the field; English dominance in Scotland was shattered for a generation.

Bruce spent his final years consolidating the kingdom and seeking international recognition. The 1320 Declaration of Arbroath, addressed to the Pope, contains the famous line:

“…for, as long as but a hundred of us remain alive, never will we on any conditions be brought under English rule. It is in truth not for glory, nor riches, nor honours that we are fighting, but for freedom—for that alone, which no honest man gives up but with life itself.”

Bruce died in 1329 at Cardross, probably of leprosy or a stroke. His heart was removed, taken on crusade by Sir James Douglas (as Bruce had requested), and eventually buried at Melrose Abbey. His body lies in Dunfermline Abbey beneath the memorable inscription: “Here lies the good King Robert Bruce, the deliverer of Scotland.”

Legend vs. History

Both Wallace and Bruce rapidly passed into legend. Blind Harry’s Wallace (c. 1477) turned Wallace into a superhuman folk hero, while John Barbour’s The Brus (1375) did the same for Bruce in more aristocratic fashion. By the 1995, Mel Gibson’s Braveheart fused the two men’s stories, gave Wallace a painted face that belonged to later Highland warriors, invented a romance with the French princess Isabella, and had Bruce betray Wallace at Falkirk (in reality Bruce was probably on the English side that day, but there is no evidence he fought against Wallace).

Yet the core truths remain powerful: a common-born knight who refused to bow, and a noble who risked everything and won. Together they turned a desperate rebellion into a viable kingdom.

Legacy

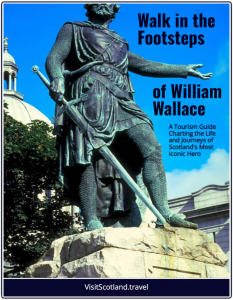

The Wallace Monument (1869) towers over Stirling, its hall of heroes dominated by a brooding statue of Wallace clutching a massive claymore. The Bruce is commemorated by statues in Edinburgh, Stirling, and Bannockburn itself, where the 1964 visitor centre and 2014 rotunda mark the battlefield.

Every year on Burns Night and St Andrew’s Day, Scots still toast “The Immortal Memory” of Wallace and Bruce. In an independent Scotland or a devolved one, their stories remain touchstones of national identity (flawed men who, in the darkest hours, chose to fight for a free Scotland).

As the Declaration of Arbroath put it seven centuries ago, they fought not for glory or riches, but for freedom alone. In that, at least, the legend and the history are one.